The Man Who Would Be King

When the Red Army began its dogged advance towards Berlin in 1944, the Military Police brought with it reams of information about political undesirables. There were plenty who fitted the bill - Ukrainian nationalists, Polish guerrillas, Czech dissidents, even communists themselves (Stalin preferred to train his own communists, just in case they got above themselves).

With Poland and Ukraine tied up, Austria - an Axis force - was not expecting a miracle. Vienna fell in April 1945, and few outside the country mourned. The city was divided into French, British, American and Russian zones, a tricky arrangement that would inspire Carol Reed's classic movie The Third Man. Midnight arrests became a common feature of life in the city, and the black market thrived.

One of the scores of men rumoured to be involved in marketeering at that miserable time was a fifty-two year-old named Wilhelm Habsburg-Lothringen. He was arrested in late October 1947. But it was not the marketeering - real or imagined - that proved his downfall. A Grand Duke of a non-existent empire, he had once been a candidate for the throne of Ukraine. In Stalin's eyes, this was more than enough to seal his fate.

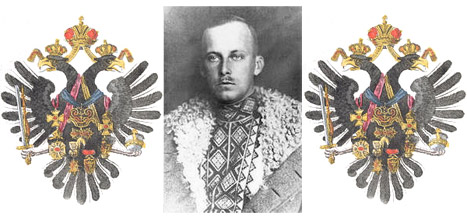

Above: William Habsburg-Lothringen, or 'Vassily the Embroidered', as he became known in the Ukraine. Here the Duke is sporting traditional Ukrainian folk costume - he published a book of Ukrainian poetry in 1921, and was the leading candidate for the throne.

Wilhelm Franz Habsburg-Lothringen was born in 1895, the youngest child of Archduke Karol Stefan. At that time, the Habsburgs ruled over some twenty nations. The Emperor Franz Joseph I was largely a popular figure throughout his lands, yet it was a time of flux: the Hungarians had won the status of dual monarchy, the Poles had taken the upper hand in Galicia, and the Czechs, Serbs and Ukrainians were all clamouring for more rights.

Within this melting pot, identities became blurred. Zywiec lay in Western Galicia, and Grand Duke Karol Stefan's children were brought up to speak Polish as well as German and other European languages. Karol Stefan was a popular figure amongst the Poles - he later married two of his daughters to Polish princes. Yet in the eastern part of Galicia, Ukrainians were in the majority, especially in the countryside. Ukrainians had lobbied for a partitioning of the kingdom along ethnic lines - still remaining under the Habsburg Crown - with Lviv as capital.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the chips were up in the air once more. And by 1916, all kinds of projects were being bandied about, one of which being that Karol Stefan would become King of a reborn Polish state. Meanwhile, his youngest son Willie - now twenty-one - was prodded in the Ukrainian direction.

Wilhelm was given command of the Ukrainian 'Sich' Riflemen, and he saw service in Galicia, a region that was brought to its knees during the conflict. The young Archduke was deeply moved by the plight of his fellow Ukrainian soldiers, and his dreams of an independent Ukraine were forged. He became fluent in the language, and proudly sported Ukrainian national costume whenever possible. The Ukrainians gave him the affectionate nickname, 'Vasyl Vyshyvanyi' - Vassily the Embroidered' - he had emerged as the candidate for the throne.

When Austria began to sense its downfall in 1918, the new Emperor Charles sanctioned all kinds of promises to his subject peoples. But it was too late. What's more, the nations themselves were seizing the initiative. From afar, England and America appeared positive about a reborn Poland, but little encouragement seemed forthcoming for Ukraine. As Poles strove to consolidate their position, Ukrainians declared a republic in Eastern Galicia. Key buildings were seized in Lviv and Ukrainian flags were raised. Yet the Poles were in the majority in that city, and had been for generations, and the young fought back. After street to street fighting for several weeks - with children fighting on both sides - the Poles won.

The Galician Ukrainians were defeated, yet the Poles cut a new deal with the Ukrainians who had lived under Tsarist Russian rule. Together, a Polish-Ukrainian army marched on the Bolsheviks, reaching Kiev itself. The Polish Marshal Jozef Pilsudski believed in a federation of nations, but when the campaign unravelled and his army was pushed back, things looked bleak for the Ukrainians once more. The Poles managed to push the Red Army back from the gates of Warsaw, but Polish Conservatives blocked Pilsudski's policies for an independent Ukraine, signing most of the eastern lands to Soviet Russia in 1921. Lviv and the surrounding region remained in Poland.

For Wilhelm Habsburg, this was a disaster. His loyalties were now firmly in the Ukrainian camp, a position that now clashed with many of his family members. His father remained in Zywiec in the newly-reborn Poland, as did most of his siblings. Yet with Ukrainian hopes dashed, Wilhelm dropped his Habsburg title and adopted 'Vasyl Vyshyvanyi' as his official name. He published a book of Ukrainian verse, and set about raising money for the Ukrainian cause from exile.

The next few years were of little joy for Wilhelm. The defeated Ukrainian government that had tried to launch itself in Lviv was now in exile in Vienna. He joined them there for some time, but the former Imperial capital was light years away from the merry metropolis of 1913. Poverty was the norm, and inflation astronomical. Wilhelm tried to scrape together funds for his Free Ukraine manifesto, and he remained in contact with key exiled figures. But it was for the most part a losing battle. Now inhabiting an altogether different world to the palatial one of his youth, he spent some time working as an estate agent in Spain. He also spent time in Paris, but in 1935, a case was brought against him - together with a French actress companion - for allegedly trying to raise money for the 'Ukrainian crown'. He left France under a cloud, and eventually resettled in Vienna.

When the Nazis took power, they were suspicious of Wilhelm, and they had him put under surveillance. (The exiled head of the Habsburgs, Otto, had himself opposed Hitler from the outset). But Vasil remained, albeit in increasingly dire straits. On the eve of war, Wilhelm was apparently boarding with an elderly school teacher. He stayed on in Vienna throughout the conflict. Meanwhile, in occupied Poland, his eldest brother had been arrested by the Nazis for Polish sympathies. Finally, Vienna fell in April '45 and Berlin followed within a fortnight.

Wilhelm, an impoverished Archduke, offered plenty of grist for the rumour mill in the ghoulish world of post-war Vienna, with its bombed out palaces and rip-off merchants. There was talk that Vasil was making ends meet on the black market. There were also records of a job at a chemical factory. Either way, the Soviet police picked him up in the Autumn of 1947. By then, the Ukraine was firmly under the Russian heel, and Wilhelm was transported to the infamous Lukyanivska prison in Kiev. He was incarcerated as a so-called 'English spy.' Reports appear to confirm that Wilhelm died there a year later, but Austrian prisoners of war testified that he perished in Vladimir Volynski, as late as 1955, having suffered appalling treatment at the hands of his captors.

Comments

Anyone with german roots will never be a good president or king in eastern Europe. By the way he was a poser, pretending to be a Ukrainian just to get the power.

ReplyI agree!

ReplyI think Vasil Vyshivany would have been a good president for a present-day Ukraine (or a king - if the monarchy would be introduced there)

Reply