The Congress of Vienna

If Vienna's Hofburg had been struck by a rogue meteorite in the Autumn of 1814, Europe would have been in quite a fix. In fact, things would have been nigh on disastrous. Virtually all the big names on the continent had gathered for what was to be the most magnificent assembly of the century. The purpose: to redraw the map of Europe after twenty years of warfare. Two emperors, four kings and more princes than you could shake a sceptre at - all were given apartments at the Imperial palace. These nobs were followed by half the aristocracy of Europe, together with the most celebrated wits, actors, singers, dancers, confectioners (and courtesans) of the day.

The purpose of the Congress may have been earnest, but the style in which it was carried out was flamboyant in the first degree. None of the grandees wanted to seem like a stingy stoat, and they were falling over themselves to lavish hospitality on each other. The Congress was an endless whirl of balls and banquets: "Le Congres ne marche pas,' quipped the aging lothario, the Prince de Ligne, 'il danse'.

That said, there was at least one chap who wouldn't have been overly upset if the meteorite had crash-landed on the Hofburg. Bonaparte. It was the defeat of Napoleon that had enabled the old guard to launch the Congress. And in their opinion, it was his mess that they were having to clean up. The crowned heads were thus celebrating the fall of Napoleon - the main reason why the Congress was so famed for its merry spirit. They were popping champagne corks over that bugger 'Boney'.

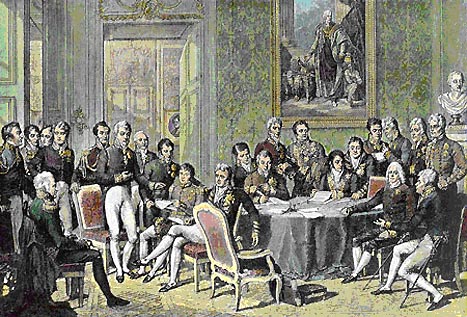

Above: The crowned heads of Europe exchange thoughts at the Congress of Vienna, mediated by the ambitious Count Metternich (centre)

The Congress was already six months down the line when the biggest bombshell of the season broke. The Monster had escaped....! News of Napoleon's getaway from Elba arrived right in the middle of one of Count Metternich's balls. The dancefloor emptied quicker than you could say scheisse, and the generals were obliged to sober up rather quicker than they had expected. Just a few weeks later Napoleon was in Paris, marshaling his troops.

As we all know now, fortune was not to smile on the Corsican adventurer. Wellington and Blucher rallied their forces and defeated Bonaparte at Waterloo on June 18, 1815. Just a week beforehand, the final documents of the Congress had been signed. This time, the Allies were not taking any chances. Napoleon was imprisoned on an island so remote that not even Houdini would have been able to escape.

The Bones of Contention

Visitors to Vienna at the time of the Congress wrote rhapsodic accounts of all the merriment. Nevertheless, there was some serious business to be done. The map of Europe was unrecognisable following Napoleon's conquests. What's more, Boney had got up to some dastardly tricks, what with freeing serfs and other such mischief. Hence the arena was set for some major power-broking.

Several decidedly sober snakes were to make their mark on the assembly. Chairing the Congress was Austrian Count (later Prince) Metternich, in future years amongst the most hated men on the continent. And into the fray slipped Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, crafty diplomat extraordinaire. Talleyrand had managed to be at the top of every French regime, be it Revolutionary, Royalist or Bonapartist. "A shit in a silk stocking' is how Bonaparte described him. At Vienna, Talleyrand launched a major charm offensive, one of his chief weapons being his maestro chef.

As the Congress danced, for some nations, Napoleon's demise was no laughing matter. The Poles for one were in trouble, having thrown in their lot with Bonaparte in the hope of regaining their independence. That independence had in fact been taken away by Austria, Prussia and Russia in 1795, and considering that those three countries were now victorious, things did not look rosy. As one English observer recalled:

'The grand subjects in discussion were the future conditions of Poland, Saxony and the Italian States - in fact, all those points in which political expediency appeared to be in opposition to justice... It was the difficulties arising on these subjects which caused the proceedings of the Congress to be so long... and for so many just and honest men to be perverted from their ways.'

Suffice it to say that the great powers at Vienna were not looking to create a brave new world. The Slave Trade may have been condemned, but even France continued human-trafficking until 1848. What in effect happened was a restoration of the pre-Bonapartist status quo. Poland was not reborn, although a tiny Congress Kingdom was created with the Tsar as king. Krakow clung on to a tenuous free city status. Meanwhile, exiled kings and princes returned to their thrones - Sardinia, Sicily, Tuscany, Modena and more. And of course, as had already been agreed, Louis XVIII returned to power in France.

Whilst it may not have been a great day for liberalism, many historians argue that the Congress managed to avert major European conflicts for many years to come. However, as the events of 1848 proved, the clock was ticking for the Ancien Regime.