The History of Vilnius

Legend has it that Vilnius was founded in the early fourteenth century by the mighty Gediminas, Grand Duke of Lithuania.

After an eventful day's hunting, the Duke was seized by weariness, and he decided to take a nap. Yet barely had he fallen asleep when a terrible apparition appeared before him. It was a gargantuan iron wolf that seemed to howl with the strength of many hundred beasts. Troubled by this ghastly vision, the Duke sought the wise druid Lizdeika. All was ordained. Lizdeika enlightened the Duke that he should found a city on the spot where he had slumbered. The city would be as strong as the Iron Wolf, and the howls echoed the grandeur of a city whose glory would ramify across the world. Gedimanas liked this idea, and lo, he founded the city, naming it after the River Vilnia.

In reality, we know that there was already a significant settlement in this valley at that time, replete with a castle of sorts. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of life here since paleolithic times. However, it is generally accepted that Gediminas transfered the Lithuanian capital from Trakai to Vilnius, and it was in his day that the city gained a fresh spring in its step.

Over the following centuries, the destiny of Vilnius was to be closely intertwined with that of Poland. It all began in 1325, when Gediminas married his daughter to the future King of Poland, Casimir the Great.

Lithuania, a powerful yet still predominantly pagan country, was in need of alliances, and hence began a tentative process of Christianisation. The crucial step was taken in 1385, when Jogaila, grandson of Gediminas, was courted by the Poles as a husband for Jadwiga, heir to the Polish throne. Lithuania was to be an equal partner in a personal union with Poland, with Jogaila as both King of Poland and Supreme Prince of Lithuania. His cousin, Vytautas, remained in Vilnius as Grand Duke, whilst Jogaila himself - as King Jagiello - moved to Cracow. The new King was obliged to convert to Christianity, as were many of the Lithuanian nobility.

Over the next few centuries Vilnius developed into one of the great European cities. The city already had a well-established Jewish community (possibly since as early as the eleventh century) and Gediminas himself had settled many German merchants. In 1387, Jogaila strengthened mercantile status with the fortuitous rights of Magdeburg law. Trade and artisanal craft flourished, and there was notable freedom of religion, with Catholic, Orthodox, Jewish and Karaite communities all well-established.

Polish soon became the language of the upper classes, but the gentry remained proud of their descent and strongly attached to their native lands. They tended to regard themselves as 'Gente Lituani, natione Poloni.' (Lithuanian origin, Polish nationality). In 1569, when the Jagiellon dynasty was running out of heirs, and Lithuania threatened in the east by Russia, a second union was signed that united the countries into a single state, not unlike the Union of England and Scotland in 1707. The Lithuanian parliament was dissolved, and the the 'Commonwealth of Two Nations' was born.

After the death of King Sigismund II (1572), who was especially attached to Vilnius, not least on account of his liason with a Lithuanian princess, monarchs were elected, and in 1595 the main Royal seat moved from Cracow to Warsaw. The entire body of the Polish-Lithuanian gentry was entitled to take part in the elections, and each region voted their own representatives to Parliament. It can be argued that this so-called 'noble democracy', which enfranchised about 10% of the population, represented the most democratic system in Europe, although that it is also remembered that the status of the peasantry remained backward in relation to several Western nations.

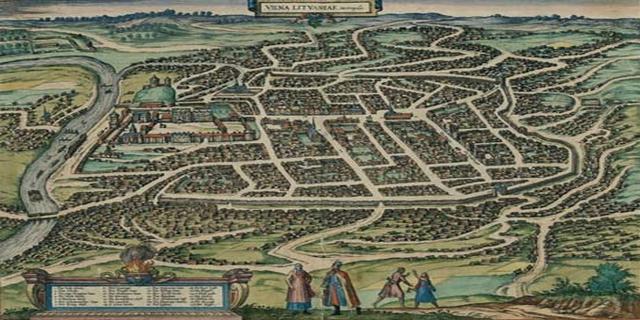

The accession of Warsaw did not spell immediate decline for Vilnius. The Transylvanian Prince Stefan Batory, elected King of Poland and hence Grand Duke of Lithuania, had a soft spot for Vilnius and he upgraded the recently established Academy to University status in 1579. Throughout the sixteenth century, an increasing number of imposing stone buildings appeared in the city, including the lower castle of Sigismund II, and numerous nobleman's palaces and churches.

The seventeenth century saw friction with the Reformation, yet the religious persecution that was commonplace in Western Europe was markedly lacking in the Commonwealth. Two major disasters shook Vilnius, being the fire of 1610 and the calamitous occupation by Russian forces in 1655, in which several thousand of the city's inhabitants were slaughtered. After the expulsion of the Russians, splendid architecture continued to be built - it was during the seventeenth century that Vilnius acquired the baroque accent that has survived until this day.

As it was, the wars of the seventeenth century had weakened the Commonwealth, and political corruption became increasingly pronounced. The last King, Stanislaw August (r. 1764-95), tried to encourage the reforming spirit but the consequences of reform were invasion by Russia, which was uneasy about a rejuvenated neighbour, let alone a liberal one. Three partitions took place dividing the Polish-Lithuania lands between Russia, Austria and Prussia. Vilnius fell to Russia in the final partition of 1795.

Barely a decade had passed before fresh hopes emerged for the recreation of a Polish-Lithuanian state. Napoleon Bonaparte appeared to be sympathetic to the Polish-Lithuanian cause and two legions joined him as early as 1796. However, it was not until 1806 that the Corsican finally set foot on the former lands of the Commonwealth, and there were setbacks from the start. What's more, the extent of the Emperor's devotion to the Polish-Lithuanian cause is highly debatable, even though he created a small Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, and referred to the 1812 campaign as his 'second Polish War.' The Grande Armee arrived in Vilnius in 1812, and Napoleon spent a fortnight in the Archbishop's Palace (now the Presidential seat). Thousands of the Polish-Lithuanian gentry had joined the ranks. However, as we all know, the campaign ended in disaster. For generations afterwards, sorry tales of frost-bitten soldiers were passed down by families in the Vilnius region.

All looked pretty gloomy for Vilnius in the wake of Napoleon's defeat, but the city had an unexpected Indian Summer. Tsar Alexander I had shown sympathy with the Polish-Lithuanian cause as a young man, and he allowed a patriot of the former Commonwealth, Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, to oversee the development of the University. It soon became the outstanding place of education in Eastern Europe, with one of the largest student bodies on the continent. Many distinguished figures were educated during this period, including the legendary Romantic poets, Juliusz Slowacki and Adam Mickiewicz. The latter's immortal line.'Litwo, ojczyzno Moja!' ('Lithuania, my Fatherland!') echoes the very specific relationship between the two nations. Mickiewicz wrote in Polish, but it was at this time that several scholars began to show an interest in Lithuanian folk culture. The work of Simonas Stanevicius and Simonas Daukantas, sowed some of the seeds for the eventual coming of a new Lithuanian identity.

In 1831, a major Uprising in Warsaw against the Russian occupiers was unleashed, and it soon spread to Vilnius. The corresponding repressions were harsh and the University was closed - it would not reopen until after the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917. A second Uprising took place in 1863, again with tragic results. In the Vilnius region as a whole, stringent measures were then taken to stamp out the Lithuanian, Polish and Belorussian languages.

During the First World War, real prospects of independence emerged for many Eastern European nations. However, matters were deeply complicated here, as by and large, a polarisation had emerged that divided those that spoke Polish, Lithuanian or Belarussian. Furthermore, many of the city's large Jewish population spoke Yiddish or Russian. At that time, less than 3 percent of Vilnius's population spoke Lithuanian, although the Lithuanian language was predominant in many nearby regions. A Council of Lithuanians had proclaimed the restoration of a state, but soon afterwards the newly born Polish state saw to it that the city was seized by General Lucjan Zeligowski (1920). Vilnius was absorbed into Poland and the Lithuanians were obliged to settle for a state that focused on Kaunas as its capital. Bitterness remained between the two sides, and in the 1930's, Lithuanian speakers in Vilnius found themselves increasingly alienated, dwindling to 1% of the overall population. However, defying simplistic categorisation, historians can even find examples of Polish speaking nobles - albeit a distinct minority - who 'crossed over' to the new Lithuanian cause. One such man was Oskar Milosz, uncle of the celebrated Polish poet Czeslaw.

Although the city itself survived, World War II was to alter Vilnius irrevocably. The Soviets deported many of the Polish and Lithuanian intelligentsia to Siberia, and the Nazis later led the eradication of the huge Jewish population and a significant proportion of the remaining Polish intelligentsia. The Germans aimed to divide and conquer, and they attempted to play off ethic groups against each other, with tragic results. The Soviets returned in 1944, and their regime was not pushed out until 1990. The majority of the remaining Polish population was compelled to relocate to the new Poland in 1946, and Russification began in earnest. The Lithuanian language itself was repressed. However, Vilnius began to grow again, following an influx of settlers from neighbouring regions in the early sixties. Lithuanian identity continued to grow, and a sense of solidarity began to unite the Baltic nations. The Lithuanians ultimately threw off the Soviet yoke in 1991, following a clash with troops at the Vilnius Television Tower, in which fourteen people died and several hundred were injured.

Lithuania proved to be one of the most successful countries in adapting to the shock of the free market system, and Vilnius led the way as the country's capital. In 2004, Lithuania joined the EU in the first wave of its expansion, alongside nine other countries. Although it has not all been a bed of roses, Lithuania's relations with her European neighbours have been positive, and a steady rapprochement with Poland has developed over the last few years.

Comments

Hi Does anybody know the modern Lithuanian town names of Poland Gajowka, Wilno and Gerwiaty Wilno approx 1930/40s. I know Wilno is now Vilnius but wanted cannot find any reference to Gajowka and Gerwiaty. My grandad was born in Wilno in 1922 and we are trying to track down more info on him

ReplyHello! This is a lovely website. Vilnius is so interesting. I'm super interested in Lithuania and it's my biggest dream to go there one day . Hopefully soon! Lots of love!!

ReplyGreat website. Complicated area history. Trying to find information on ancestors from Lida and Nacz or Nacza. Mother Wanda Adamowicz born in Slonim. Her Mother Agata Maculewicz nee Gabis born in Nacza. My mother said somebody in family was very important, minor noble? but no other details. Mother's father Jozef Boleslaw Adamowicz had all sons and one daughter. Sons Mietek, Marek, ? All taken away to Siberia February 1940? Mietek returned. Information very much appreciated. I can read Polish and German, Russian not so much but possible. Would like to visit soon.

ReplyI was born in Vilno. My grandfather was also taken by the Russians to Siberia where he perished. My hubby and I are going to Vilno again this fall and will be taking a tour of the famous KGB police station there to have some closure. Would love to share my family experiences with you.

ReplyI would like to know about an old Vilnius family called 'Curjinsky' or Czurjinski' - I don't know how it is spelt! I think they had a historic family home, maybe on a hill? My husband said that when Napoleon invaded onlt the Ratzvills and the Czurjinski stood against them. That was his mother's family. He died 20 years ago and I am trying to find some details.Thank you '

ReplyI appreciated the content very much. I visited Lithuania on business a number of times in 1995, 1996 and 1997. On the first visit in June of 1995 a news article about the erection of a bust of Frank Zappa has left me wondering every since about why and I have not been able to find an answer. It is necessary to note that the citizens of Vilnius and of Lithuania have a pride of country that is very commendable.

ReplyFrom what I read about the Frank Zappa bust, it's simply because they could! It was a test of their independence. An "If we're really free and independent then we should be allowed to erect a bust of Frank Zappa who literally has nothing to do with Lithuania" to which the government replied "Um sure, go ahead!"

ReplyThe history is very intertwined. Looking for my grandfather Adam Adamowicz born 1865 Name changed to Adam Adams. Suppose to be from local noble family. Came to USA thru Ellis Island.

ReplyI am searching for information about my grandfather Harry Winisky, a Painter in Vilius at the turn of the century 1800-1900

Replyhello my name is greta im from lithuania i dont rite english very good. i live in siauliai. well i can tell about vilnius it is not just country its a big country it is near the latvia, belarus and poland its a verry very beautiful therre is very much threes and there is a summer its very hot, spring not very hot, in winter its very cold and in atumn its not very cold... I LOVE THAT COUNTRY!!!!! KLEPKE313

ReplyHey man. Im doing a project about Vilnius. So I know the mayor. Its Juozas Imbrasas. Thanks for this site. I wouldve failed without it!

Replyi went to vilnius in april, i went to look up my family but came to a dead end my great grandfather was i was told mayor of vilnius but don,t know his name anybody out there help me please

ReplyPast mayors of Vilnius from wikipedia Vytautas Bernatonis – 1990–1993 Alis Vidūnas – 1995–1997 Algirdas Čiučelis – 1997 Rolandas Paksas – 1997–1999, 2000 Juozas Imbrasas – 1999–2000, 2007–2009 Artūras Zuokas – 2000–2003, 2003–2007, 2011–2015 Gediminas Paviržis – 2003 Vilius Navickas – 2009–2010 Raimundas Alekna – 2010–2011 Remigijus Šimašius – since 2015

Reply